article copied from

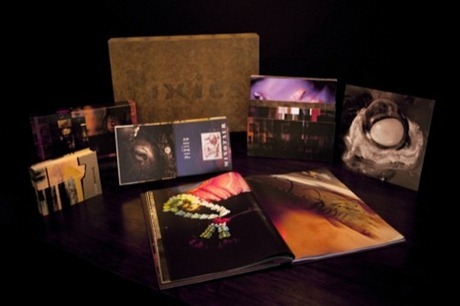

Iconic graphic designer Vaughan Oliver has spent more than three decades creating beautifully weird, wonderful and influential work, helping reinvent the approach to record sleeve design. Perhaps most famous for his designs for record label 4AD’s bands such as the Pixies and Cocteau Twins, Oliver’s career has also spanned work with oddball director David Lynch, and projects in fashion, film, dance and fine art.

Ahead of his talk later this month, Visceral Pleasures: 30 years in 60 minutes, Design Week spoke to Oliver about his celebrated ambiguous style, the importance of collaboration, and the death of designing for record sleeves.

What will you talk about in the lecture?

My life and work - 30 years in 60 minutes! Collaborations I’ve made, the way I work - using ambiguity and mystery, and my ad-hoc, intuitive, iconoclastic approach to typography – i.e I don’t know what I’m doing.

Where did your interest in typography come from?

I studied graphic design but really wanted to be an illustrator. In the late 1970s before the boom of the 1980s I lived in Newcastle Upon Tyne and studied at the poly. I still didn’t know what graphic design really was but I wanted to do something in the area of music but hadn’t touched on typography. Back then I was ignorant of its potential, as I think it was taught a lot more drily. Nowadays the man on the street knows the word ‘font’. When I came out of college I was working designing packaging and drinks labels, and that introduced me to typography. I was obliged to use it do had to look more closely and study what was working. When I started making sleeves I started playing with big letters next to little letters and big, evocative mark-making – playing with that in different contexts and trying to respond to the imagery I already had.

How would you describe your work?

When I have to describe it for things like this [the talk] or an exhibition, I’d say it’s a slightly obscure an obtuse way of looking at things. I suppose I grew up in a period where the visual pun was prevalent in graphic design – a one-liner – but I enjoy things being a lot more open to interpretation, which is very useful working in areas like designing for music.

How did you first get involved with the record label 4AD?

I met a man called Ivo [Watts-Russell, joint-founder with Peter Kent of 4AD] – they were just two guys working in a studio. Ivo knew I wanted to work in that field, so I put my foot in the door and wouldn’t take it out. I used to bump into him at a lot of gigs and persuade him he needed things like logos and visual consistency.

So how did you approach designing sleeves and other music projects?

All that stuff was done with a lot of collaboration and collusion with the bands. With something like the Pixies, for example, the lyrics are full of images but I didn’t necessarily use those images directly - apart from Monkey Gone to Heaven - but I’d listen to it and discuss the themes with Charles [Thompson III, aka Black Francis, lead singer of The Pixies]

So how did the Pixies artwork evolve?

We had a mutual affection for Lynch films, and Charles liked the idea of male nudity on a record sleeve [an image of a bald man with a hairy back is shown in the Come on Pilgrim EP sleeve]. Incidentally there was male nudity on some of photographer Simon Larbalestier’s work I’d seen. I’d liked his work - he graduated from the RCA and the hairy man was on the wall at his show. A lot of the images I use are pre-existing – I see a lot of photographers’ and students’ work and think ‘oh that’s good’ – but I’m not working on anything that sounds like that. Then you hear something it would be perfect for – but that might be four years later. I’m a very demonstrative art director. Half the job’s done when you’ve chosen the right photographer and made the link between his work and the record. It’s very rare that I’d stand over their shoulder.

Have there been any pieces that are personal highlights in your career?

Probably the Doolittle [Pixies 1989 album] artwork. It’s not about my work though – it’s about people being affected in their formative years but the power of music and graphic design together: when it works, it’s a fabulous thing. People have said they got into graphic design because of [Doolittle] – but it’s about hitting people in their formative years with that combination. It’s not about big clients.

4AD is the music I’d have bought – it wasn’t just a record company to me, it was like putting sleeves on my own records. Back then it was part of the culture- I’d be talking about the sleeve with the band in the day and going to their gig in the evening.

With most music downloaded and record sales dwindling, how has the field of designing for record sleeves changed?

I don’t think it’s great area for design at the moment – sleeves have become a niche market. The disappearance of the packaging has meant that the once the sleeve was a gateway to the music, but now record collections are a list of MP3s with no tangible reference points. I think it’s a shame it has become a niche market. Once it was much more demonstrative –everyone got the vinyl and had that pleasure, now its just for those who can find it or afford it.

What are you working on at the moment?

I’m doing some more work with David Lynch, and a new label coming out of Belgium, Brooklyn Bridge records…

What advice would you give to students trying to get into graphic design now?

Work hard – find your own voice, for fuck’s sake don’t follow trends. Lots of people want to work in the way others do - they don’t realise the market will die. Be inquisitive and curious and don’t settle for something easy. Keep on pushing.

Vaughan Oliver receiving his honorary Masters degree from UCA in 2011

0 comments:

Post a Comment